Ever since we experienced the highly enjoyable financial panic of 2008, people have been casting about for someone to blame. And why not? Every great crisis needs an equally great bad guy. It's fun, and it increases the chance that your abject misery will eventually get optioned into movie rights.

But there's one bad guy that's proving surprisingly popular: The homebuyers themselves. Why not? They were the irresponsible borrowers who took on too much debt, far too soon, and sent the economy into crisis. This is America, after all. If you have to hate someone, you might as well hate the common man.

We're probably behind the ball on this one, seeing as how the recession ended while we were suffering a particularly bad hangover during the entire month of June, 2009, so we should probably let this one go. But we're immodest fellows here at the Strawman Blogger, so late or not, we're going to put this myth to rest.

Don't worry. You can thank us later.

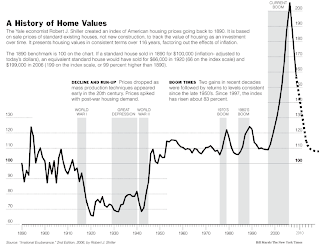

First, let's get a few things out of the way. Homeowners assumed too much debt in the crisis. That much is obvious:

And it also had very predictable consequences:

But participating in a crisis doesn't make you culpable for it. When you buy a home, you work with a team of people: Real estate agents who help you shop for a home, lenders who finance it, and industry experts who provide advice and perspective along the way. Each one earns money when you buy a home. And each one earns more money the more home you buy.

And, during the worst housing bubble in American history, each one argued that a bubble wasn't possible.

Realtors fed that delusion. In 2005, David Lereah, Chief Economist and Senior VP for the National Association of Realtors (NAR), argued that, "[t]here is virtually no risk of a national housing price bubble based on the fundamental demand for housing." In 2006, he predicted a "soft landing for the housing markets." Even as late as October, 2007, the NAR continued to peddle the line that, "[t]he speculative excesses have been removed from the market and home sales are returning to fundamentally health levels."

Nor were they alone. On August 18, 2007, celebrity columnist Ben Stein appeared on Cavuto on Business to state that, "[t]he credit crunch is way overblown ... The subprime problem is a problem, but it's a tiny problem in the context of this economy ... It's a buying opportunity, especially for the financials, maybe like I've never seen before in my entire life.

Financial firms were not immune to the excess. Abetted by the ratings agencies, which catastrophically failed to recognize the growing risks in the mortgage market, large investment banks were net long in housing until the bitter end. Even the previously responsible JPMorgan Chase, which had long avoided the collateralized debt obligation business, was eventually burned by the infamous Magnetar trade, losing $880 million on the Squared CDO alone.

But perhaps the most memorable remark came from then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, who stated, "Although a 'bubble' in home prices for the nation as a whole does not appear likely, there do appear to be, at a minimum, signs of froth in some local markets ... Although we certainly cannot rule out home price declines, especially in some local markets, these declines, were they to occur, likely would not have substantial macroeconomic implications."

Homeowners took on too much debt. More than they could afford. But they didn't do it alone. They did it on the advice of their realtors, who assured them that housing was a good investment. They did it with loans from their banks, who were eager to finance mortgages in any way possible. They did so with liquidity provided by Wall Street, who's addiction to mortgage securitization fueled the crisis. And they did it on the advice and encouragement of financial experts and the Federal Reserve itself.

Each of these actors were experts in their own field. Should home buyers have ignored their advice? Perhaps. But arguing that means admitting that the entire mortgage industry was engaged in an exercise of bad faith - providing bad advice to good people, in hopes of turning a profit.

So who was at fault, you ask? Everyone. And no one. That's the trouble with bubbles. They work because they're so damn convincing. If no one believed in them, they wouldn't happen in the first place.

Well. That, and the bankers, of course.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Moral Culpability And The Crisis: Our Least Sexy Title Ever

Labels:

debt,

financial crisis,

Great Recession,

greenspan,

jpmorgan,

realtors